Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka

Last updated: February 2023

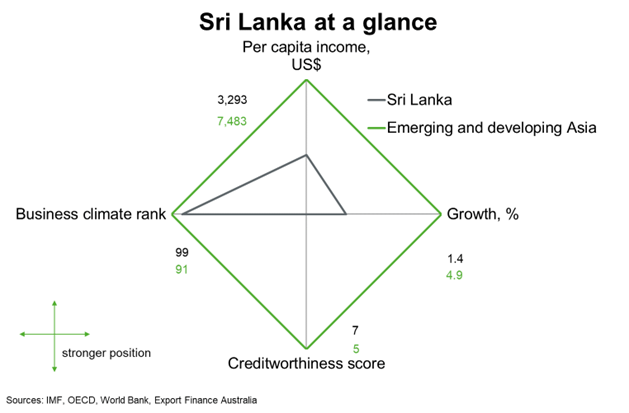

Sri Lanka remains a lower-middle-income country; GDP per capita is well below the average for emerging Asian countries. Measures of the business climate, growth and creditworthiness are also below the regional average. Public debt and balance of payments problems, political risks, security and geopolitical issues and environmental risks all remain prominent challenges. Amid these challenges, the country has a highly literate population, diversified economy and moderately strong institutions.

| The above chart is a cobweb diagram showing how a country measures up on four important dimensions of economic performance—per capita income, annual GDP growth, business climate rank and creditworthiness. Per capita income is in current US dollars. Annual GDP growth is the five-year average forecast between 2023 and 2027. Business climate is measured by the World Bank’s 2019 Ease of Doing Business ranking of 190 countries. Creditworthiness attempts to measure a country's ability to honour its external debt obligations and is measured by its OECD country credit risk rating. The chart shows not only how a country performs on the four dimensions, but how it measures up against other countries in the region. |

Economic outlook

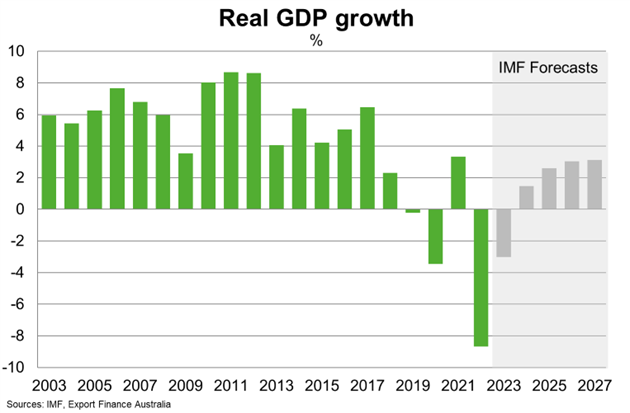

In April 2022, the Sri Lankan government announced a unilateral suspension of foreign debt repayments, amounting to a pre-emptive default on all external debt, including bonds and bilateral loans from foreign governments. The lack of foreign exchange, high inflation and depreciating rupee made it difficult to import necessary items such as food and fuel, hitting economic output and contributing to civil unrest. Real GDP fell a sharp 9.2% in 2022.

The World Bank forecasts real GDP to contract a further 4.2% in 2023. Soaring inflation (at 54% year-on-year in January 2023) and aggressive interest rate hikes will weigh on household consumption and business investment. Foreign reserves have declined below one month of imports to US$1.9 billion in January 2023, continuing to hamper the country’s ability to import essential items. Insufficient and unreliable energy supplies will remain a major constraint on economic activity, while shortages of medicine and food raise social risks.

In September 2022, the IMF and Sri Lanka reached a staff-level agreement on a US$2.9 billion (3.5% of GDP) four-year IMF Extended Fund Facility (EFF) to restore economic recovery and fiscal health. The EFF hinges on Sri Lanka receiving financing assurances to restore debt sustainability from major official and private sector creditors. Progress is being made on this front. Overall, the IMF program focuses on raising fiscal revenue to support fiscal consolidation, restoring price stability through increasing interest rates and rebuilding foreign reserves through a flexible exchange rate. Assuming Sri Lankan authorities engineer a successful debt restructuring operation and an IMF program is implemented in 2023, the economy will begin to recover from 2024. Unlocking assistance from other multilateral organisations, including the World Bank and Asian Development Bank, is conditional on the IMF funding package.

Risks to growth are significant and tilted to the downside. A slow debt restructuring process, limited external financing support, and the scarring effects of the economic contraction could prolong economic and financial distress.

Long run growth potential hinges on Sri Lanka attracting more foreign investment, diversifying trade and reviving tourism. Sri Lanka's strategic location on key shipping routes, as well as its expanded port capacity, position it well to benefit from increased trade, particularly in South Asia. Effective implementation of IMF-led structural reforms to facilitate trade and investment would boost competitiveness and support longer-term growth.

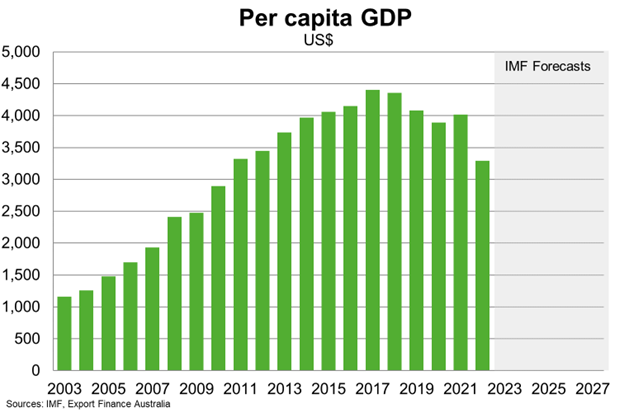

GDP per capita has fallen from above US$4,000 in 2017 and 2018 to an estimated $3,200 in 2022 due to severe economic contraction, high food inflation, job losses and a drop in remittances. The World Bank estimates the poverty rate increased to 25.6% in 2022 from 11.3% in 2019 due to the economic and financial crisis and the negative impacts on jobs, incomes and livelihoods. As a result, much of the income gains over the past decade have been reversed.

Country risk

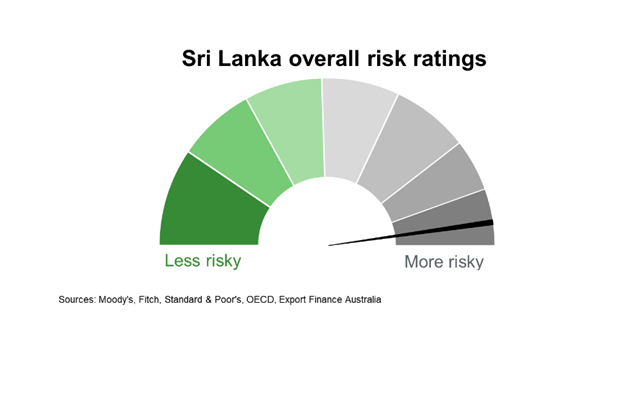

Country risk in Sri Lanka is high. The OECD has a country credit grade of 7. The government has suspended debt servicing on all public external debt, pending the negotiation of a comprehensive debt restructuring to restore debt sustainability.

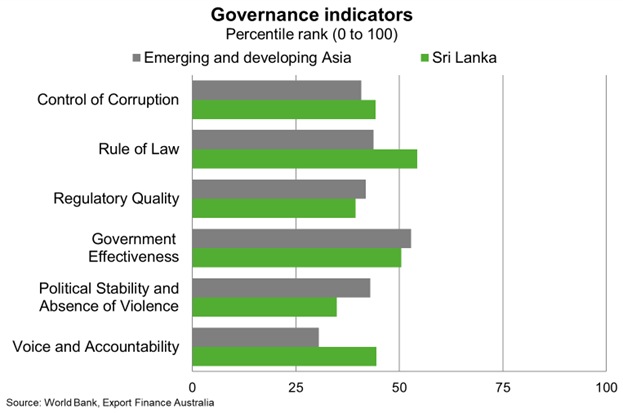

Sri Lanka’s scores on Worldwide Governance Indicators are broadly in line with the average for emerging Asian countries. Still, most indicators rank in the bottom half of all countries. Sri Lanka lags on measures of political stability and absence of violence, government effectiveness and regulatory quality. Implementation of IMF-led reforms could, over time, enhance governance and the effectiveness of economic, political and fiscal institutions.

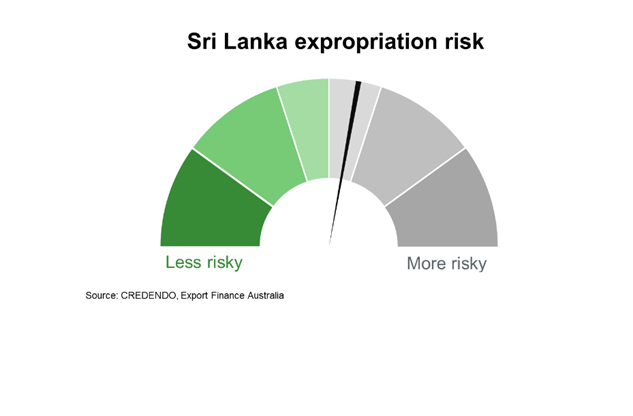

The risk of expropriation in Sri Lanka is moderate, consistent with governance scores around control of corruption and rule of law. According to the US Investment Guide Statements, the Sri Lankan land acquisition law empowers the government to take private land for public purposes with compensation based on a government valuation.

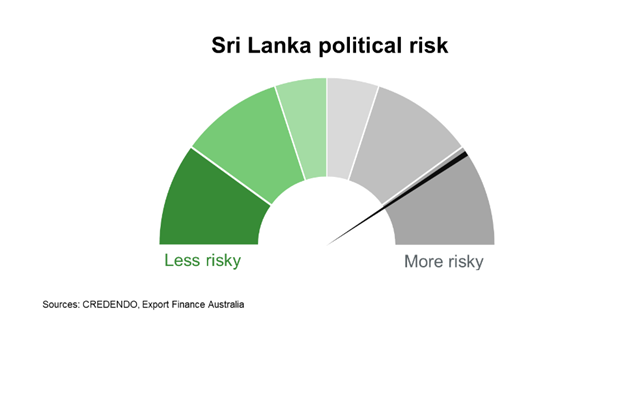

Political risk in Sri Lanka is high. The ongoing economic crisis, high inflation and persistent shortages of essential items will continue to raise risks around political stability and social unrest.

Bilateral relations

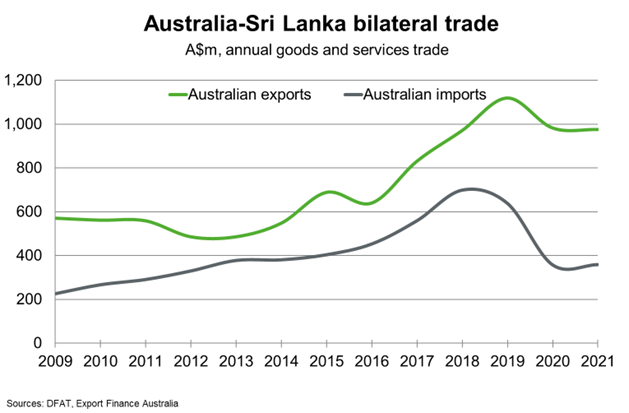

Sri Lanka is Australia’s 47th largest trading partner. Total goods and services trade amounted to $1.3 billion in 2021. Exports to Sri Lanka consist mostly of education-related travel, wheat and vegetables. Imports from Sri Lanka are made up mostly of clothing, textiles and tea.

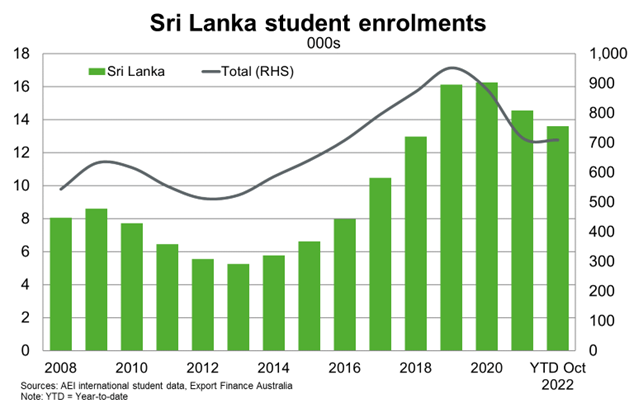

Before the pandemic, Sri Lankan students studying in Australia had been increasing significantly from a low level. Enrolments remained above 2018 levels through the pandemic. This is partly because many Australian education providers that operate in Sri Lanka, including Monash University, the Australian College of Business and Technology and the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, all offer remote learning programs.

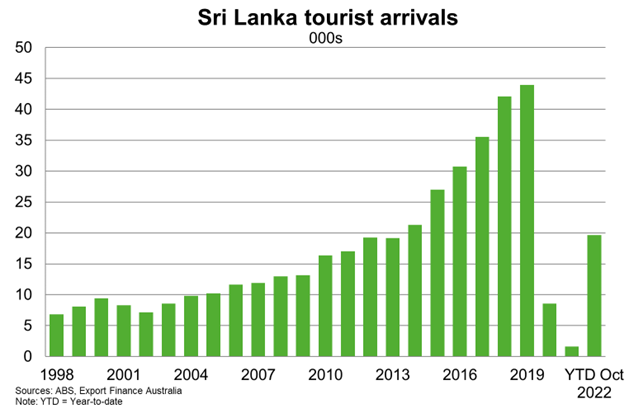

As in education, Sri Lanka had been a growing market for Australian tourism before the pandemic. The launch of direct flights between the two countries in 2017 boosted Sri Lankan demand for Australian tourism; more than 40,000 Sri Lankans visited Australia in 2018 and 2019 before the pandemic cut arrivals from 2020 to 2022. The recovery in tourism has been steady; by October 2022, tourism arrivals had recovered to around 45% of their pre-pandemic level. Another year of open international borders and pent-up demand for travel should support further recovery in tourism, and broader services exports, in 2023.

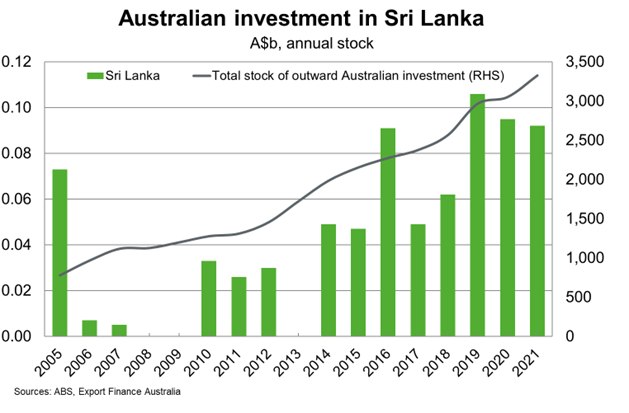

Bilateral investment between Sri Lanka and Australia remains small. Australia’s development program will support Sri Lanka’s efforts to enhance health security and advance economic development.

Useful links

Department of Foreign Affairs

Austrade