© Export Finance Australia

The views expressed in World Risk Developments represent those of Export Finance Australia at the time of publication and are subject to change. They do not represent the views of the Australian Government. The information in this report is published for general information only and does not comprise advice or a recommendation of any kind. While Export Finance Australia endeavours to ensure this information is accurate and current at the time of publication, Export Finance Australia makes no representation or warranty as to its reliability, accuracy or completeness. To the maximum extent permitted by law, Export Finance Australia will not be liable to you or any other person for any loss or damage suffered or incurred by any person arising from any act, or failure to act, on the basis of any information or opinions contained in this report.

Australia—Export profile resilient to higher tariffs

While tariffs and policy uncertainty are expected to slow global growth, the impact on Australian exports will be relatively small and largely on prices rather than volumes, according to the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA). This reflects Australia’s a) limited trade with the US and b) resource-heavy export profile.

a) Australia’s exposure to US demand is small. Direct exports to the US comprise 6% of total exports and ‘value-added’ exports to the US (which includes indirect demand via global supply chains) remains below 10%. US demand will be resilient for Australian goods where US production is small and competitors face similar (or higher) tariffs. Australian exporters may also diversify to alternative markets, as occurred when China imposed barriers on Australian exports.

b) Exports are dominated by resources for which Australia is a relatively low-cost producer. As such, many Australian exporters would remain profitable and maintain production volumes even if prices fall. However, fiscal stimulus by China (45% of resource exports and 30% of total exports) support demand for key commodities. Services and other goods exports—which tend to be more discretionary and easier to substitute—may be relatively vulnerable to weaker global growth.

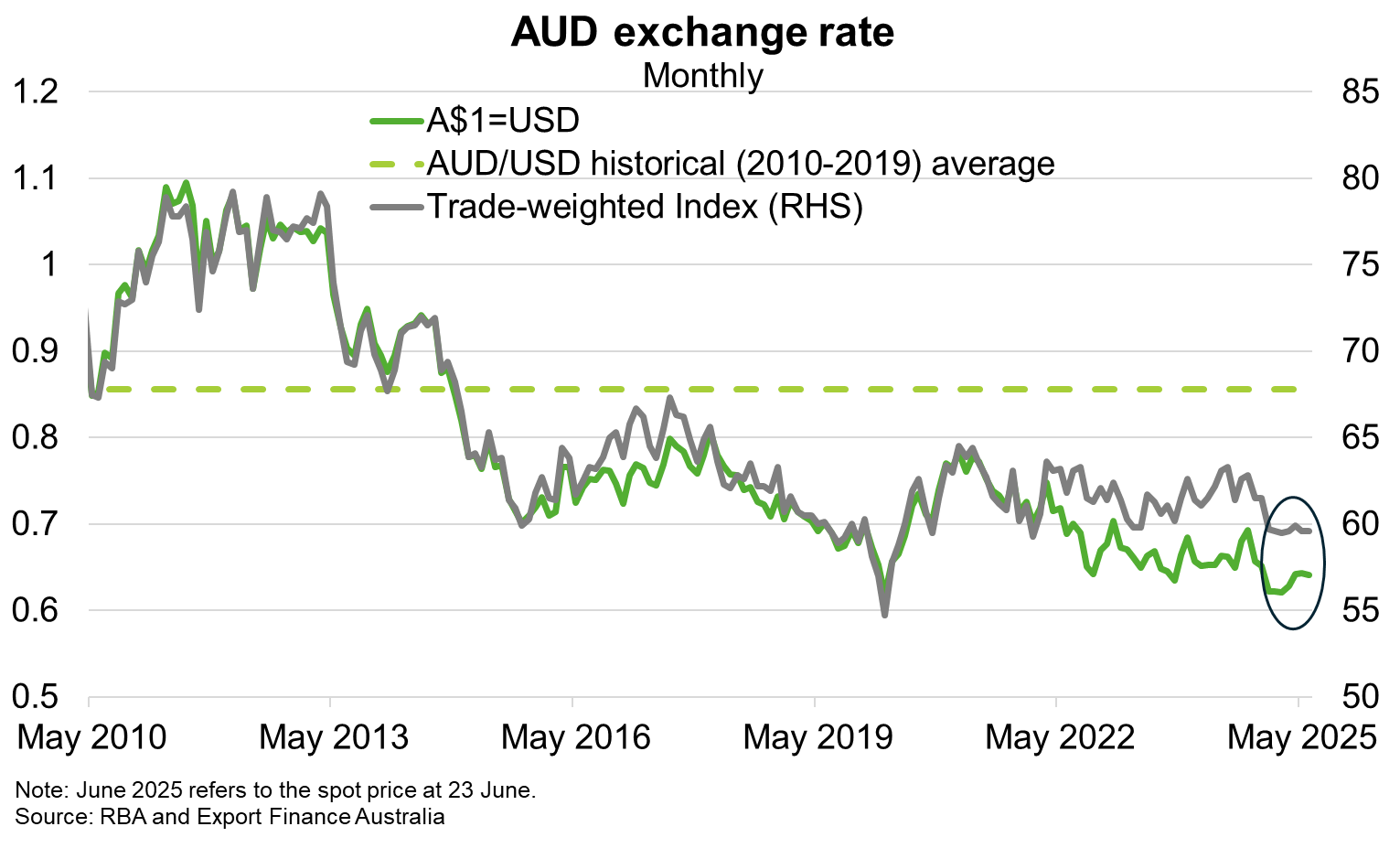

The outlook is uncertain. In particular, while the AUD typically depreciates in response to slower global growth or increased risk aversion (thereby improving Australia’s competitiveness in export markets), the AUD has been little changed in trade-weighted terms amid broad-based USD weakness (Chart). While still well below the historical average, AUD stickiness may limit its usual role as a shock absorber. The RBA also notes that while the recent US–China trade agreement reduces global growth risks, a protracted ‘trade war’ would lower GDP in Australia’s major trading partners by 3% relative to baseline by end-2027, a larger decline than during the global financial crisis.