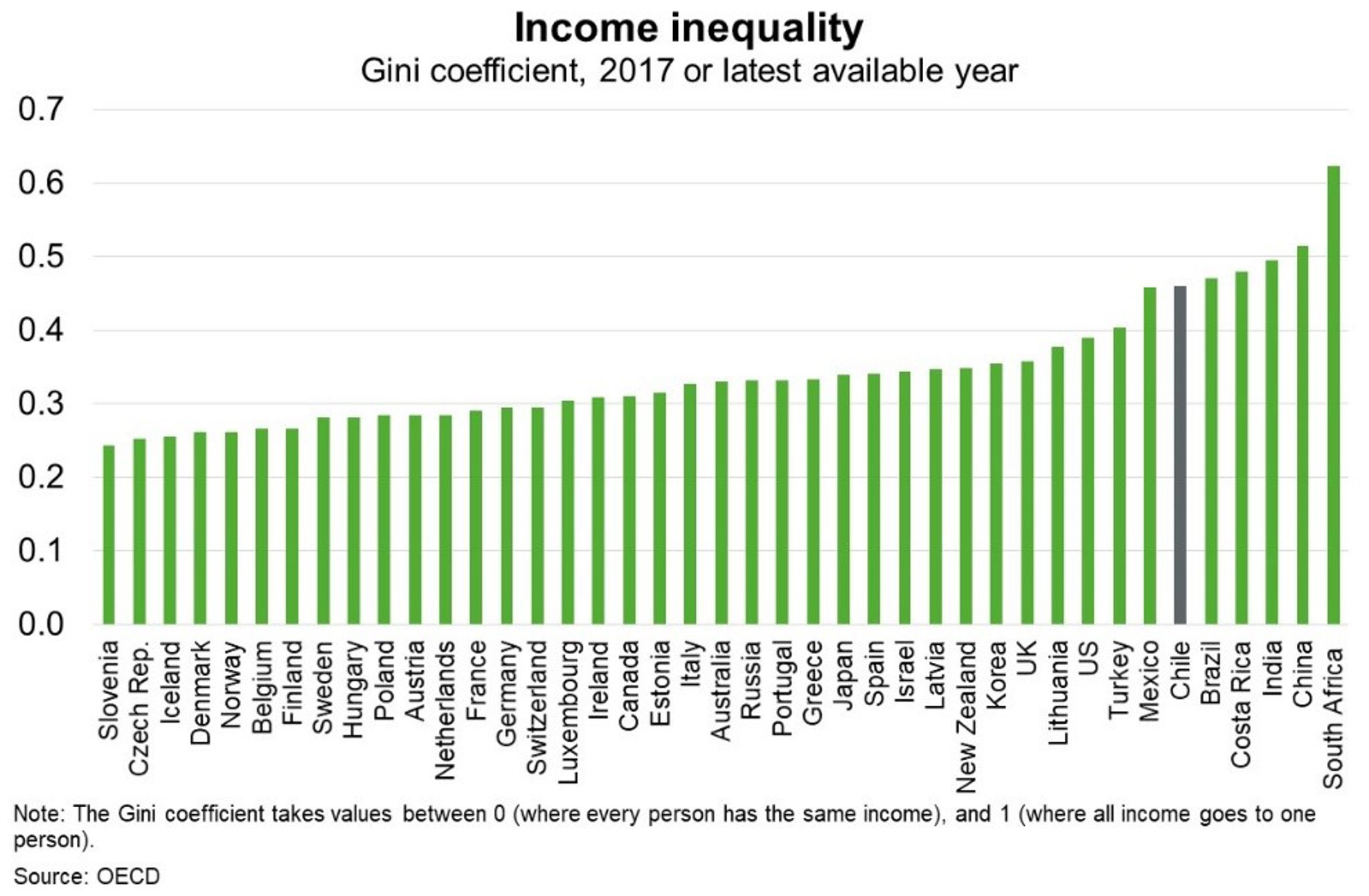

Long regarded as among the wealthiest and most stable democracies in Latin America, Chile has endured the largest mass protests in three decades. Initial agitation over a 4% rise in metro fares led to widespread clashes and demands for structural changes to Chile’s economic model. Despite years of robust GDP growth and an impressive reduction in poverty (from 30% in 2000 to 6% in 2017), income inequality remains stubbornly high (Chart). In 2017, the richest 10% still earnt 20 times that of the poorest 10%.

To quell protests and strikes, President Piñera has announced increases to the minimum pension and wage, freezes on transport and electricity prices, a reduced working week (from 45 to 40 hours), and enhanced health benefits; funded in part by higher taxes on the wealthy and withdrawals from the nation’s sovereign wealth fund. The government has also launched a process to redraft Chile’s market-friendly constitution, a legacy from the Pinochet military dictatorship (1973-90), to codify a new social pact. But despite concessions wrested from the centre-right government, protests continue while national strikes have gained wide adherence.

The longer the protests continue the greater the damage to business sentiment, investment and overall economic activity in Australia’s third largest Latin American export market. But with polled support for Pinera at just 14%, the lowest approval rating for any elected Chilean president, the ability of government to execute on policies to end the disruptions is constrained. Markets are also sceptical—the peso fell to a 17-year low against the dollar this month. As such, GDP growth will likely fall well short of the IMF’s 3% forecast next year while there will be increased costs to doing business in Chile over the medium term.