Indonesia

Indonesia

Last updated: February 2024

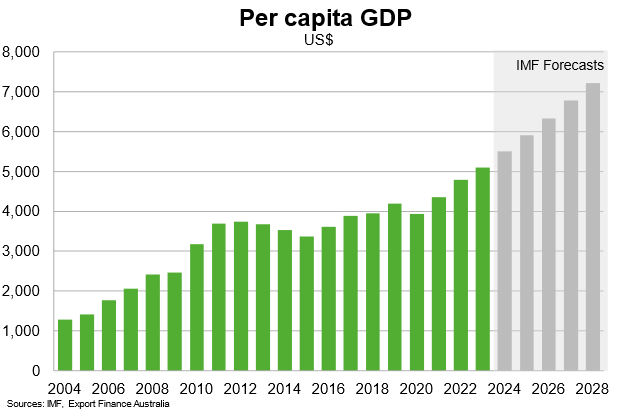

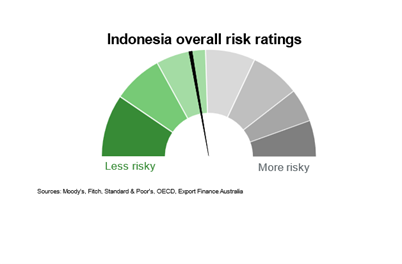

Indonesia’s economic growth prospects are slightly stronger than the average of emerging and developing Asian peers, supported by a large, growing and youthful population, and a large reserve of natural resources. Creditworthiness and business climate indicators are above the regional average. However, Indonesia’s per capita income lags regional peers.

This chart is a cobweb diagram showing how a country measures up on four important dimensions of economic performance—per capita income, annual GDP growth, business climate and creditworthiness. Per capita income is in current US dollars. Annual GDP growth is the five-year average forecast between 2024 and 2028. Business climate is measured by the World Bank’s 2019 Ease of Doing Business ranking of 190 countries. Creditworthiness attempts to measure a country's ability to honour its external debt obligations and is measured by its OECD country credit risk rating. The chart shows not only how a country performs on the four dimensions, but how it measures up against other regional countries.

Economic outlook

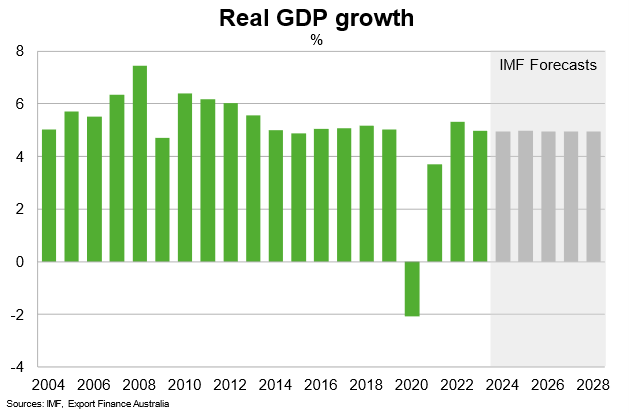

Indonesia grew a robust 5% in 2023, albeit slightly softer than 5.3% in 2022. Rising government capital spending supported increasing infrastructure development. Despite high interest rates, consumption received support from falling unemployment and cost-of-living support measures, which helped control inflation (at 2.6% year-over-year in December 2023). Manufacturing expanded as government measures to support investment in downstream commodity processing helped boost output. But exports remained muted amid lower prices for critical minerals and government-implemented export restrictions in some sectors.

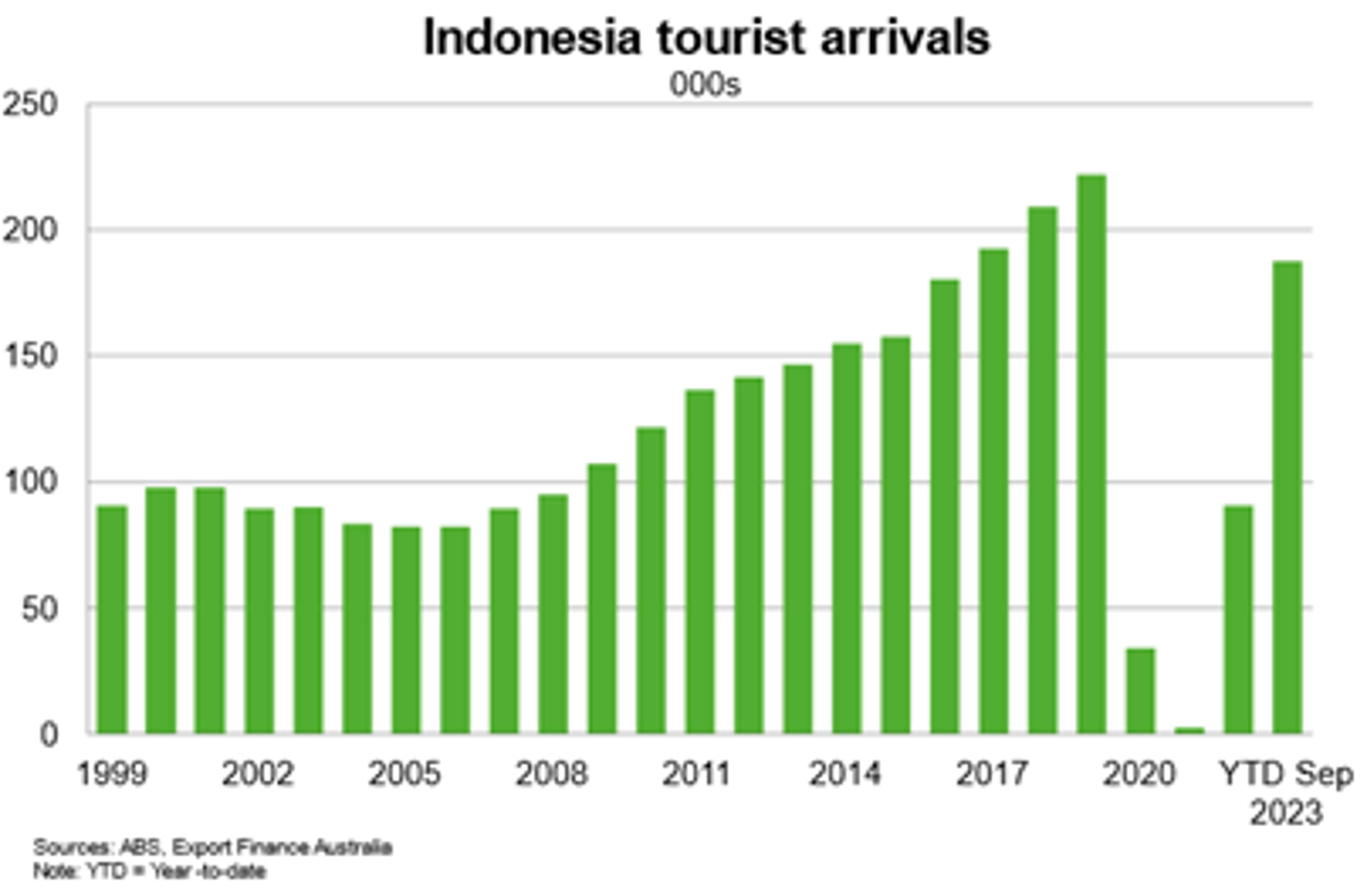

The IMF forecasts growth to remain at 5% in 2024. Domestic consumption should continue to underpin growth, through employment creation and lower inflation. Tourism arrivals should continue to rise amid increasing international travel. But exports are expected to remain subdued amid weak global demand, softer commodity prices and ongoing export bans. Export restrictions aim to attract foreign investment in minerals processing, in turn helping Indonesia reduce imports of commodity inputs. The likelihood of policy continuity following the 2024 election should support continued momentum on existing policies (around reducing corruption, increasing social support programs and enhancing investment) to help improve the business climate. The 2023 jobs decree, which has been passed into law, should help reduce bureaucracy and red tape and provide certainty for investors. Early 2024 Presidential election results suggest the government is likely to continue to implement policies aimed at boosting investment in infrastructure and social support programs, a positive for the business climate and foreign investment.

Risks are tilted to the downside. Higher for longer interest rates could continue to weigh on global demand, as can the potential for slower than expected growth in China and the US. Geopolitical uncertainty remains a prominent risk because of Indonesia’s integration in global supply chains and world trade. Climate change adds to these risks.

Longer term growth hinges on the ability of Indonesia to advance human capital development, including education, health and social protection. The IMF expects growth to average 5% per annum between 2025 to 2028, helped by the 2025-2045 National Long-Term Development Plan (RPJPN). Tax reforms are boosting government revenue, allowing the government to spend more on education, infrastructure and health while also supporting fiscal discipline. Continued infrastructure investment, including construction of the new capital city, Nusantara, supports economic activity ahead. In general, foreign investment prospects remain positive, due to Indonesia’s abundance of natural resources and development of downstream minerals processing that should boost exports and job creation over time.

Indonesia’s strong growth and reduction in poverty over the last 20 years has come as a result of expansions in infrastructure, access to electricity, urbanisation and non-agricultural employment. A bright economic outlook bodes well for income growth, as the IMF estimate that per capita incomes will reach US$7,200 in 2028, up from around US$5,100 in 2023.

Country risk

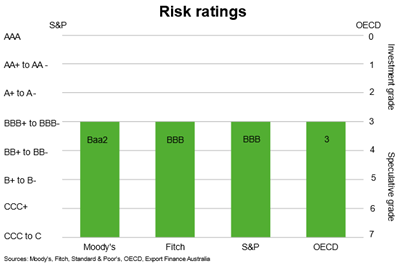

Country risk in Indonesia is low to moderate. Indonesia has an investment grade credit rating and an OECD country credit grade of 3. This indicates a low to moderate likelihood that Indonesia will be unable or unwilling to meet its external debt obligations.

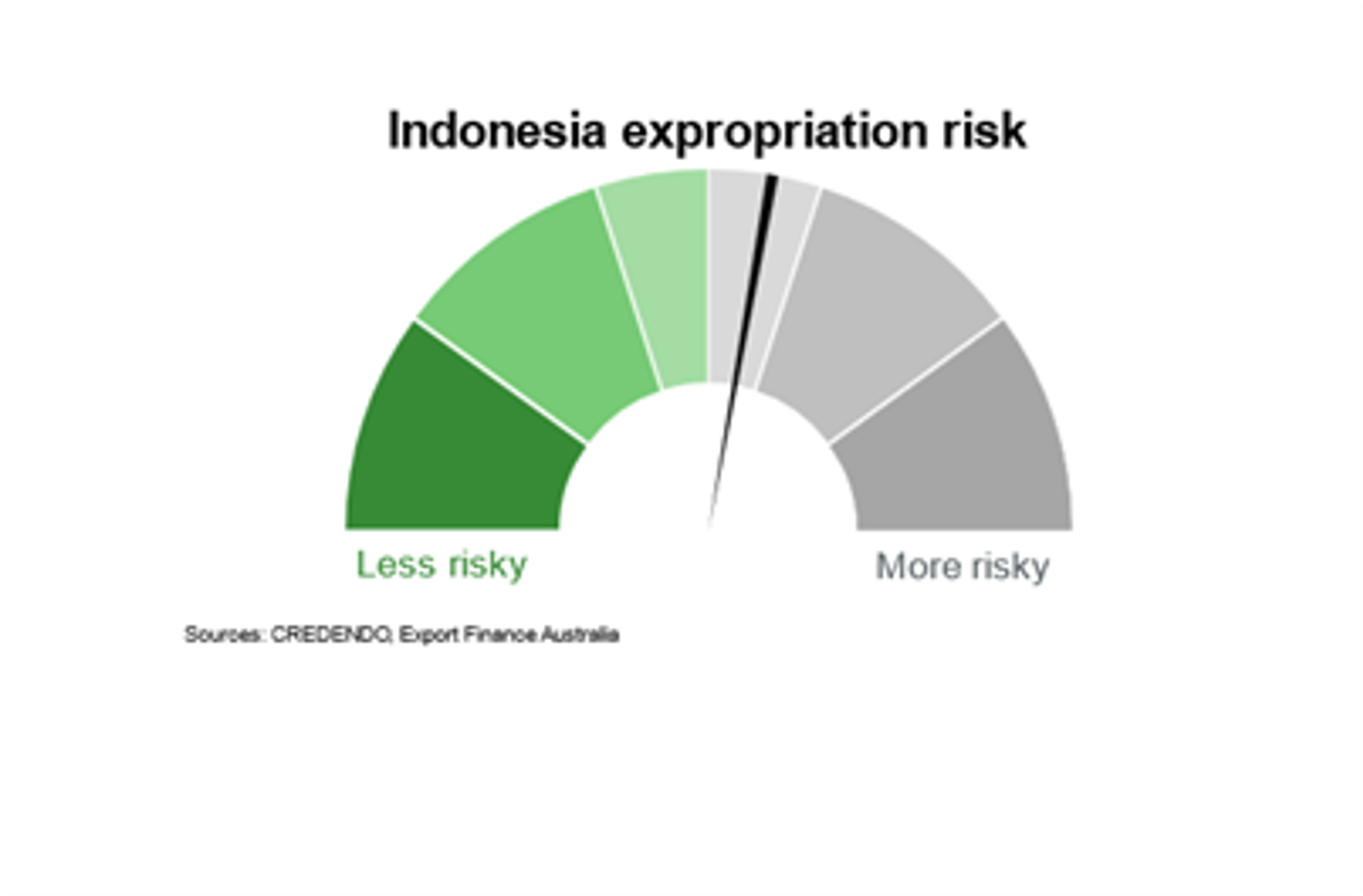

Risk of expropriation in Indonesia is moderate. According to the US Investment Climate Statements, Indonesia has a track record of economic nationalism. The 2009 Mining Law introduced a raft of measures that impact on foreign investment—including domestic processing and majority-ownership divestment requirements. For instance, the divestment regulations stipulate that all foreign miners must divest 51% of shares to Indonesian companies by the tenth year of production. As part of the implementation of the mining law and its implementing regulations, Freeport and Rio handed over majority ownership of the Grasberg mine, the world’s second largest copper mine, to the Indonesian government.

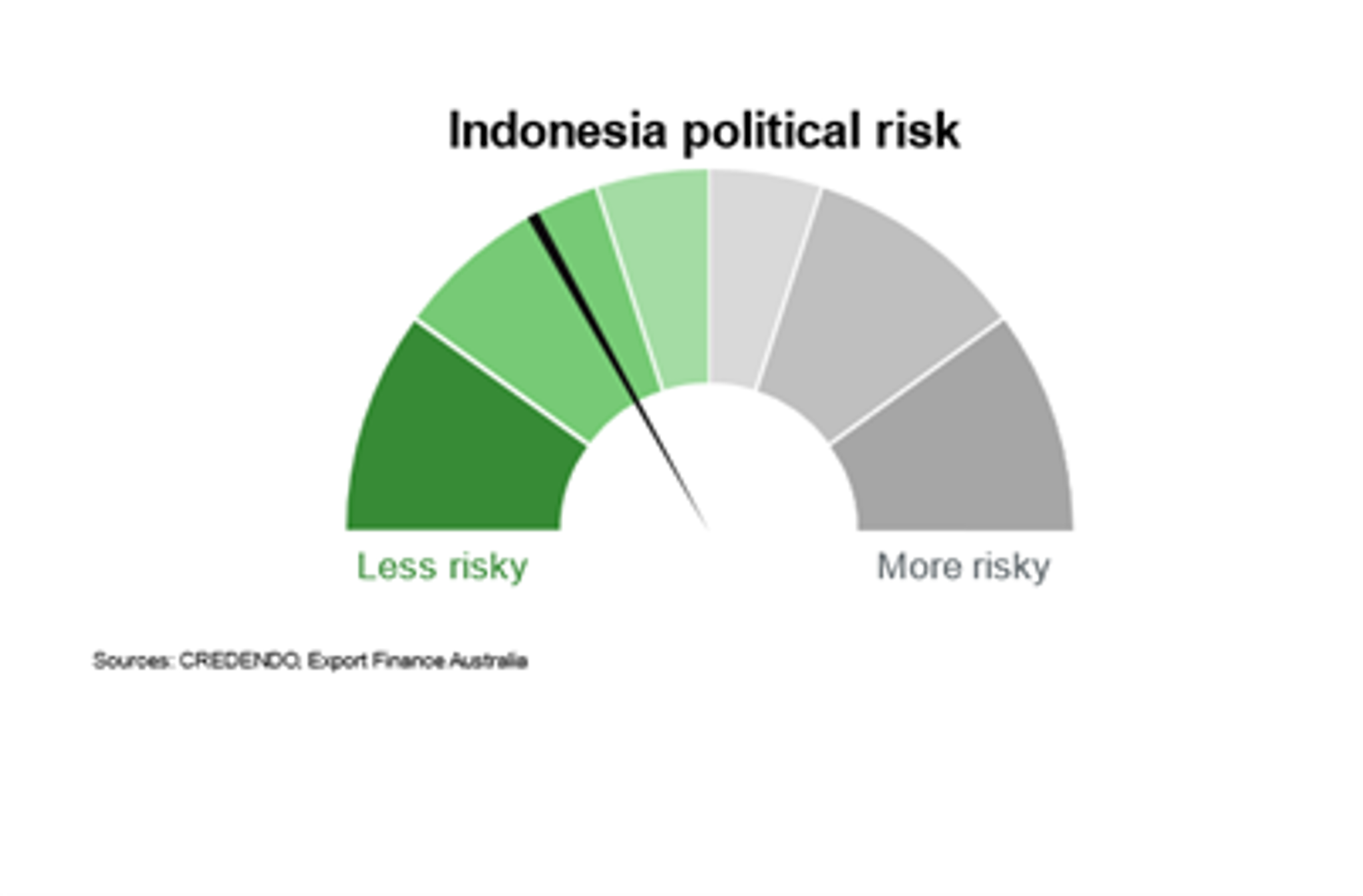

Political risk in Indonesia is low to moderate. Politically motivated demonstrations occasionally occur, but not to the extent that it damages foreign investment. Flare-ups in recent years have arisen from religious-based tensions and student protests.

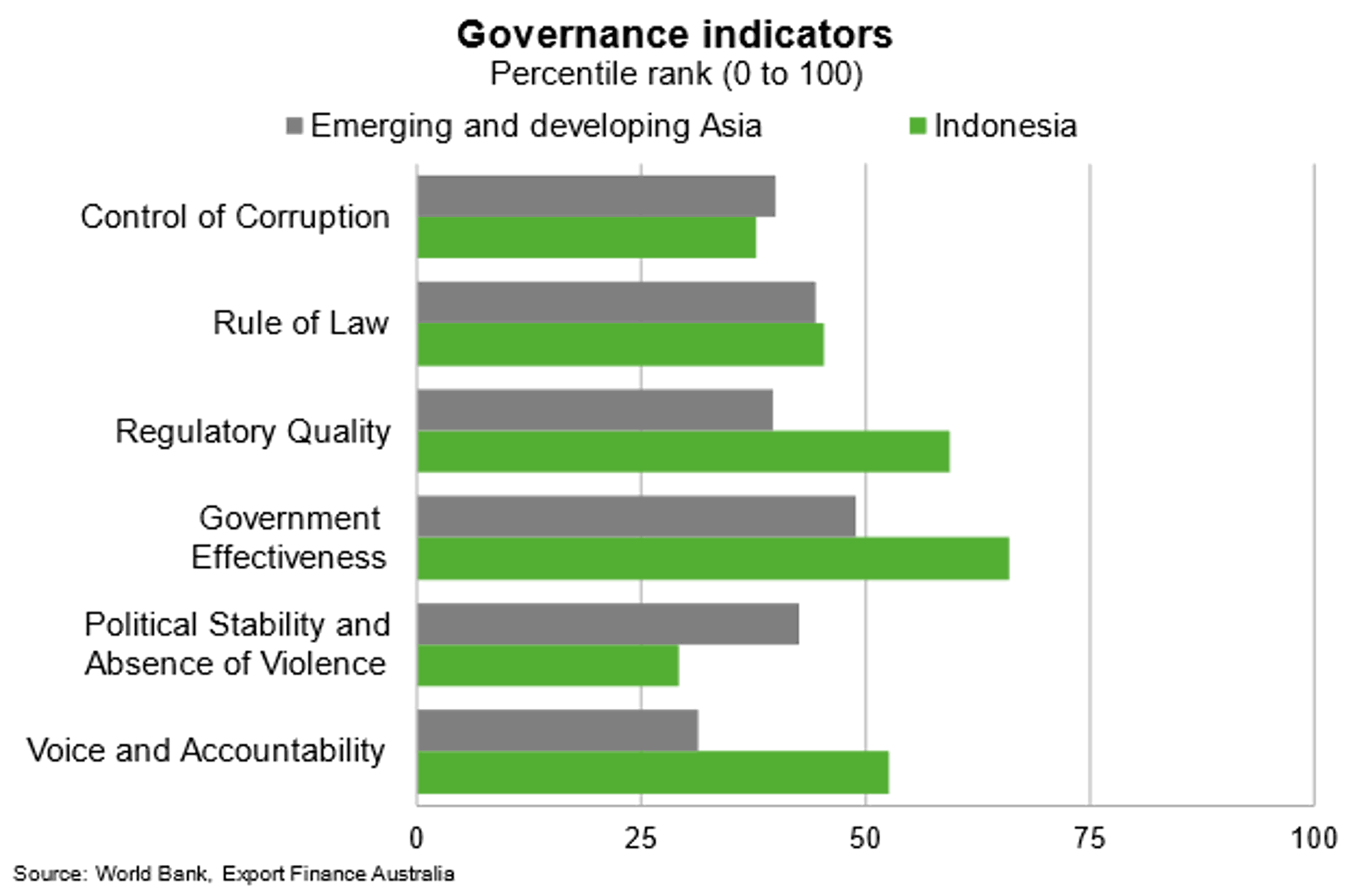

Indonesia has significantly improved on all dimensions of the Worldwide governance indicators, in part due to the passage of the jobs decree into law, building on the Omnibus bill. The bill has helped streamline regulations and simplify licensing processes, making it easier to do business in Indonesia. Control of corruption is broadly in line with the regional average. However, Indonesia lags behind the regional average on measures of political stability and absence of violence.

Bilateral relations

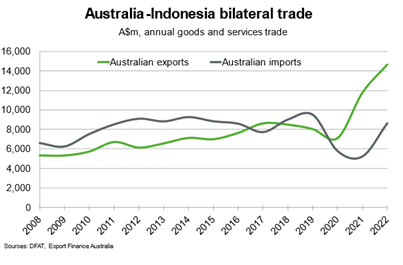

Indonesia was Australia’s 14th largest trading partner in 2022. Total goods and services trade amounted to $23.3 billion in 2022, rising more than $6 billion from 2021. Indonesia and Australia have a significant trade relationship; about 2,500 Australian companies export to Indonesia, and around 250 Australian businesses have a subsidiary in Indonesia.

Major Australian goods exports include coal, wheat, gold and iron ore. The entry-into-force of the Indonesia–Australia Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (IA-CEPA) in July 2020 has supported expansion in Australian exports over the past few years, helping businesses to take advantage of Indonesia’s robust growth.

Goods imports from Indonesia consist mainly of fertilisers, monitors, projectors and televisions The sharp rise in Australian imports from Indonesia in 2022 in large part reflected increasing fertilisers imports, as global prices rose due to COVID-19 restrictions, high food demand and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

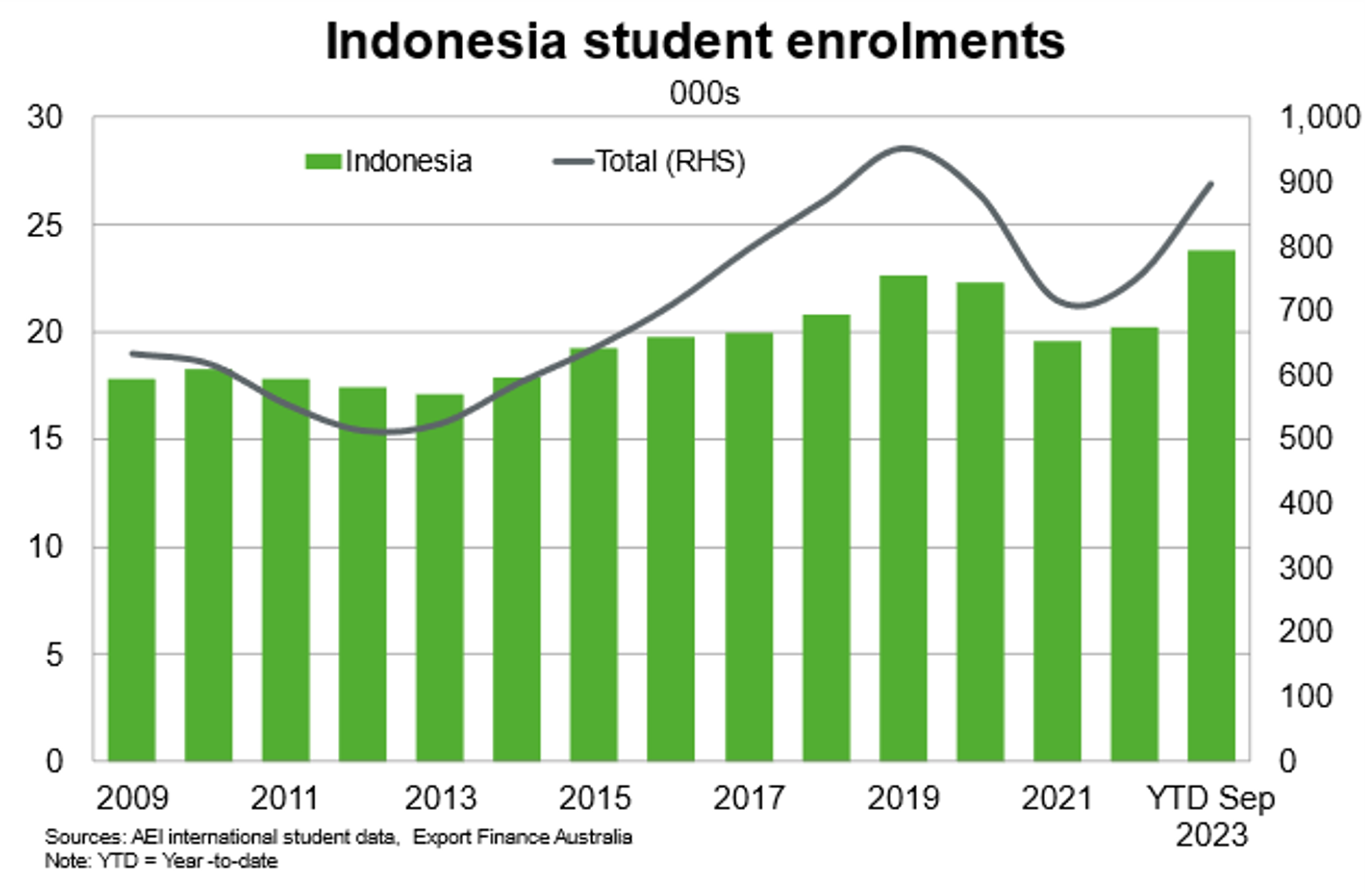

Indonesia was Australia’s 10th largest source of student enrolments in 2023. Student enrolments from Indonesia have recovered following the end of pandemic restrictions. The presence of more than 300 partnerships between higher institutions in Australia and Indonesia further support the education sector. To support the government’s economic growth objectives, Indonesia is looking to maximise the benefits of its demographic dividend, including through increased access to globally relevant education and training. The government has an ambitious target of adding 57 million skilled Indonesians to the workforce by 2030. That could open up opportunities for Australian education operators, particularly vocational education and training providers. Looking ahead, a competitive Australian dollar and another year of recovery in international travel should support continued demand for Australian education and tourism, and broader services exports, in 2024.

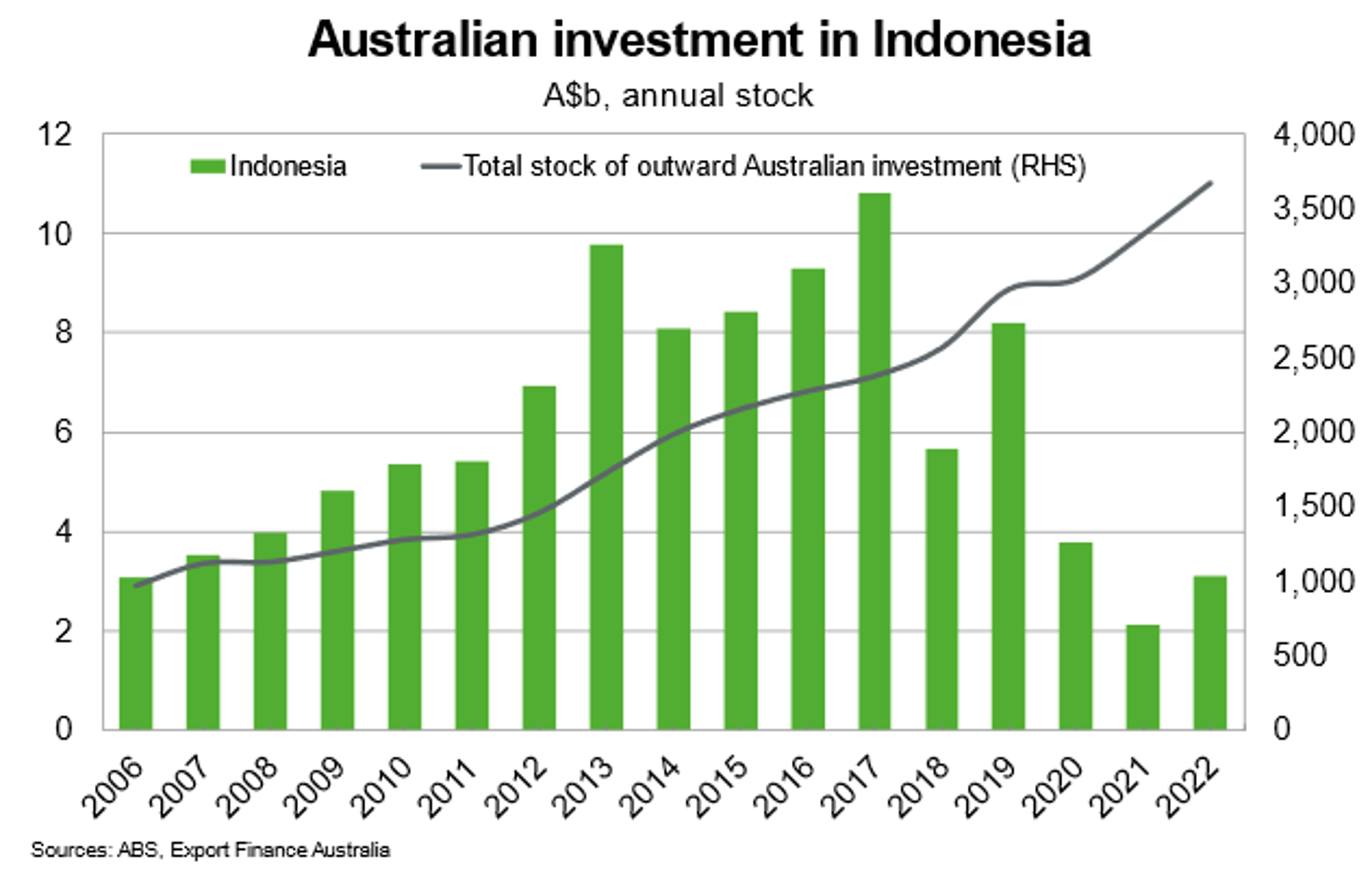

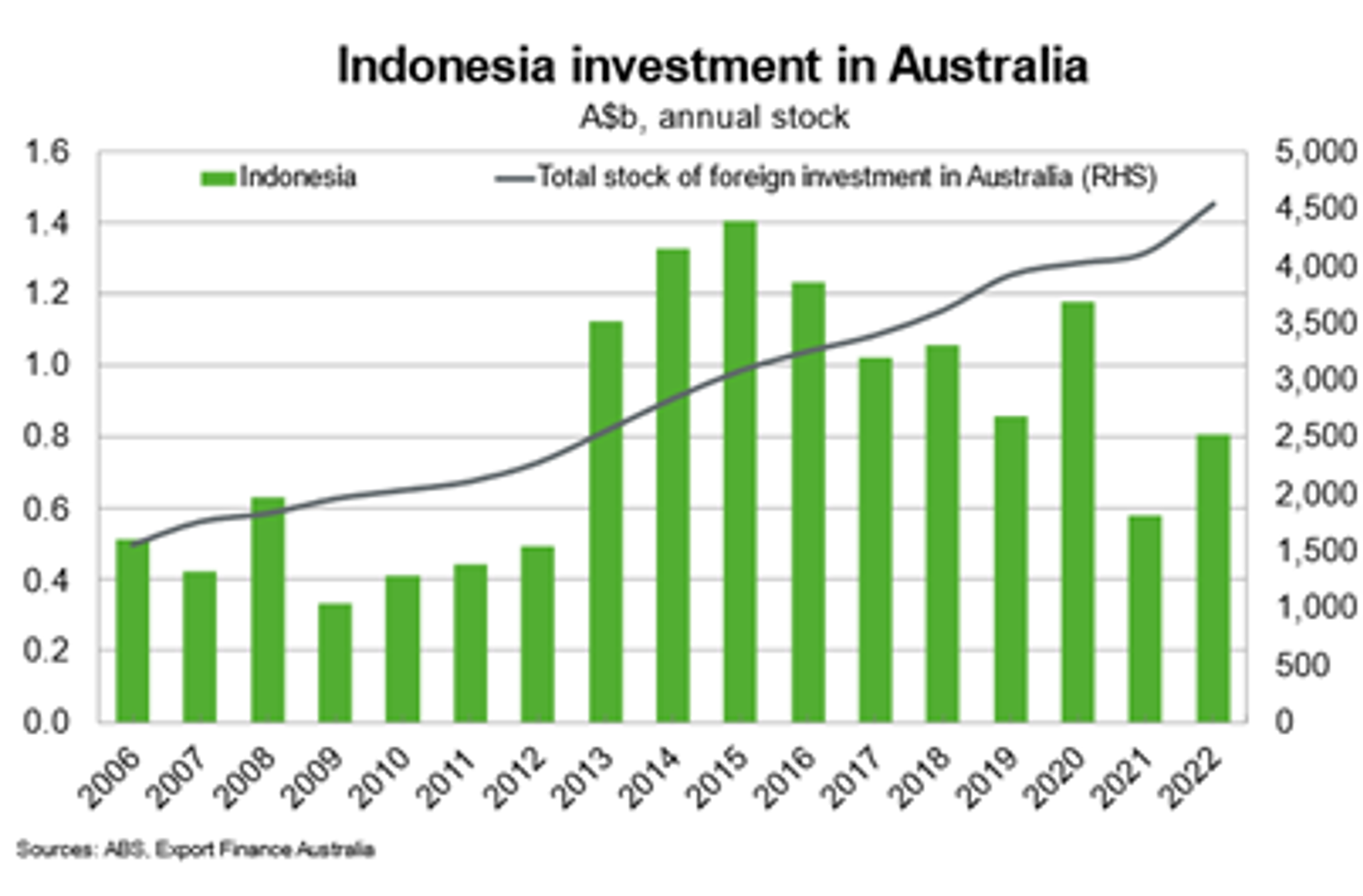

Indonesia is a small investor in Australia, owning a portfolio of about $800 million in 2022. The stock of Australia’s investment in Indonesia is larger, at $3.1 billion in 2022, increasing by 46% from 2021. The projected rise in Indonesian demand for consumer goods and services—particularly for premium food and beverages, education and healthcare, financial and ICT services and tourism—and its ambitious infrastructure investment agenda, offers significant opportunities for Australian investors and exporters.

Useful links

Department of Foreign Affairs

Indonesia-Australia Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement negotiations

Austrade