Vietnam

Vietnam

Last updated: February 2024

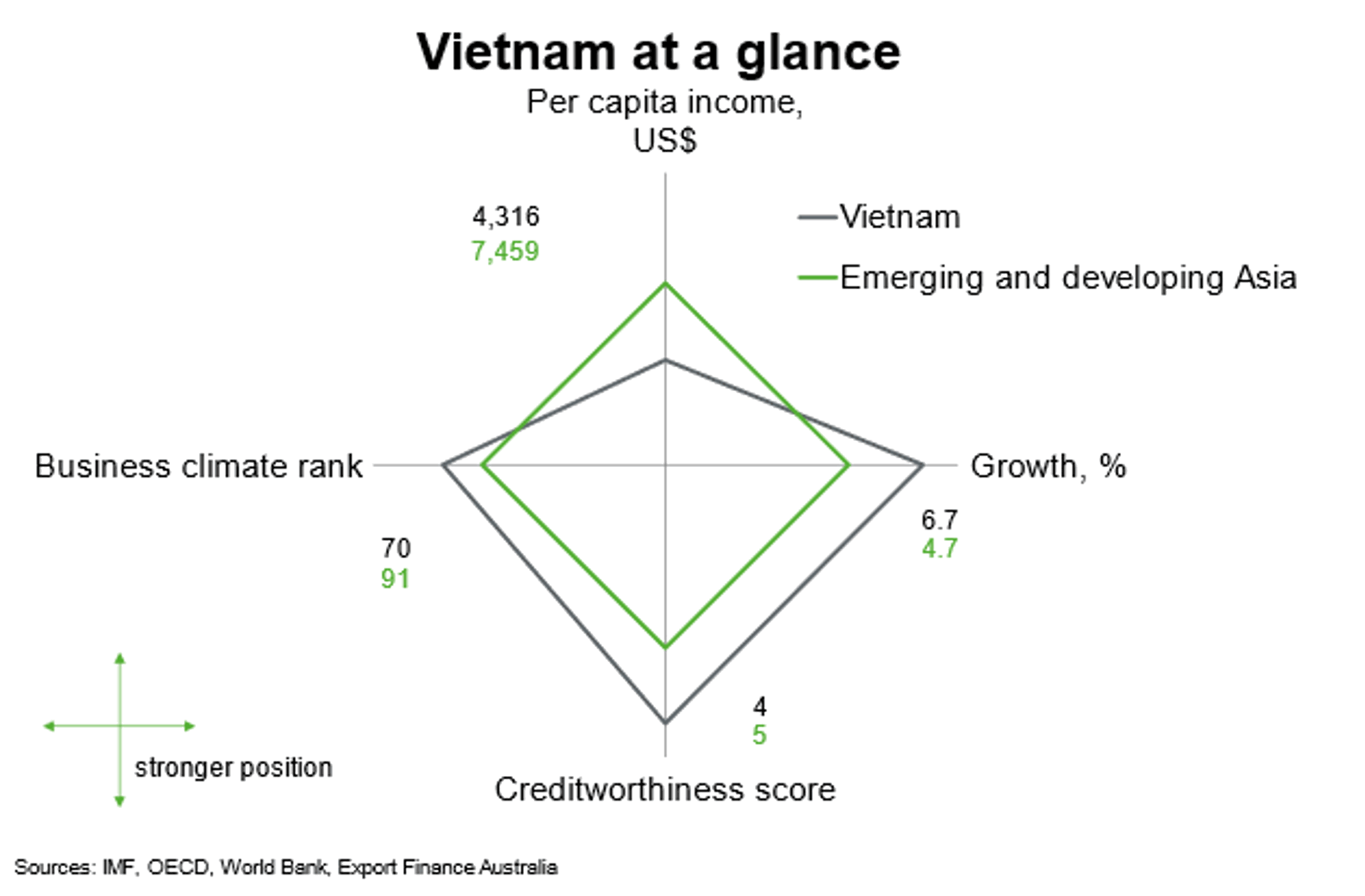

Vietnam’s transformation in the early 1990s toward a market-based economy ushered in a period of strong growth and attracted significant foreign investment. Continued economic liberalisation, anchored by several international trade deals, has fostered a strengthening in the business climate, which outperforms other emerging Asian countries. Growth is higher than regional peers. Creditworthiness is stronger than emerging Asian peers. But per capita incomes continue to lag the regional average.

This chart is a cobweb diagram showing how a country measures up on four important dimensions of economic performance—per capita income, annual GDP growth, business climate and creditworthiness. Per capita income is in current US dollars. Annual GDP growth is the five-year average forecast between 2024 and 2028. Business climate is measured by the World Bank’s 2019 Ease of Doing Business ranking of 190 countries. Creditworthiness attempts to measure a country's ability to honour its external debt obligations and is measured by its OECD country credit risk rating. The chart shows not only how a country performs on the four dimensions, but how it measures up against other regional countries.

Economic outlook

Vietnam’s economy rebounded in 2022 after two pandemic-hit years. Growth accelerated to 7% in 2022 from 2.6% in 2021 and 2.9% in 2020, driven by a rebound in services activity and robust exports. The manufacturing sector remained relatively resilient to Ukraine-related supply shocks, as production of footwear, electronics, and machinery recorded double-digit growth for most of last year. Vietnam is a competitive manufacturing and export hub and has benefited from strong FDI flows amid geopolitical tensions in the global economy, which will likely continue in 2023.

The IMF estimates GDP growth to average above 6.5% per annum between 2023 to 2027. Growth in the near term will be driven by increasing investment and tourism, as growth in manufacturing and exports moderates in line with the slowing global economy. The easing of China’s zero-COVID policy should support demand for Vietnamese tourism; before the pandemic, Chinese travelers accounted for a third of all visitors to Vietnam. The government’s Economic Support Program (worth 1.6% of GDP) should continue to support private consumption. However, tightening global credit conditions, slowing world growth and rising inflation will dampen growth. A slowdown in the US economy will weigh on Vietnamese exports; the US is Vietnam’s largest export market, accounting for 30% of total goods exports in 2022.

Risks are significant and tilted to the downside. Vietnam’s reliance on foreign demand makes it vulnerable to a sharper-than-expected global economic slowdown. Moreover, further commodity price shocks, additional tightening global financial markets and disruptions in global supply chains remain notable threats to the outlook. Weaknesses in the balance sheets of corporates, banks and households also continues to pose a risk to investment and consumption.

Over the long term, Vietnam is well placed to continue to attract trade and investment from within and outside the region. Vietnam is widely seen as a supply-chain alternative to China because of its low labour costs, educated workforce and large and growing population. The business environment has steadily improved alongside global economic integration and trade liberalisation through participation in multiple international trade deals. A track record of stability in the political and security environment is also conducive for doing business. Vietnam’s young population, alongside the increasing shift into higher-value added manufacturing and services industries, will bolster economic activity.

Longer-term challenges include the potential for increasing global trade tensions, domestic labour shortages and the reliance on large, inefficient state-owned enterprises.

Greater industrialisation, investment and trade, and rising credit demand have propelled Vietnam from a low-income to a lower-middle-income country. Continued strong economic growth and increases in minimum wages will help incomes rise to US$6,300 by 2028, from US$4,300 in 2023. As the workforce moves away from agriculture towards more productive manufacturing and services jobs, poverty rates have fallen significantly.

Country Risk

Vietnam has an OECD country risk rating of 4, which means that there is a moderate possibility of Vietnam being unwilling or unable to service its debt obligations.

The three major rating agencies have sub-investment grade credit ratings for Vietnam.

Vietnam’s scores on Worldwide Governance Indicators are broadly in line with, or stronger, than the average for emerging Asian countries. The notable exception is voice and accountability.

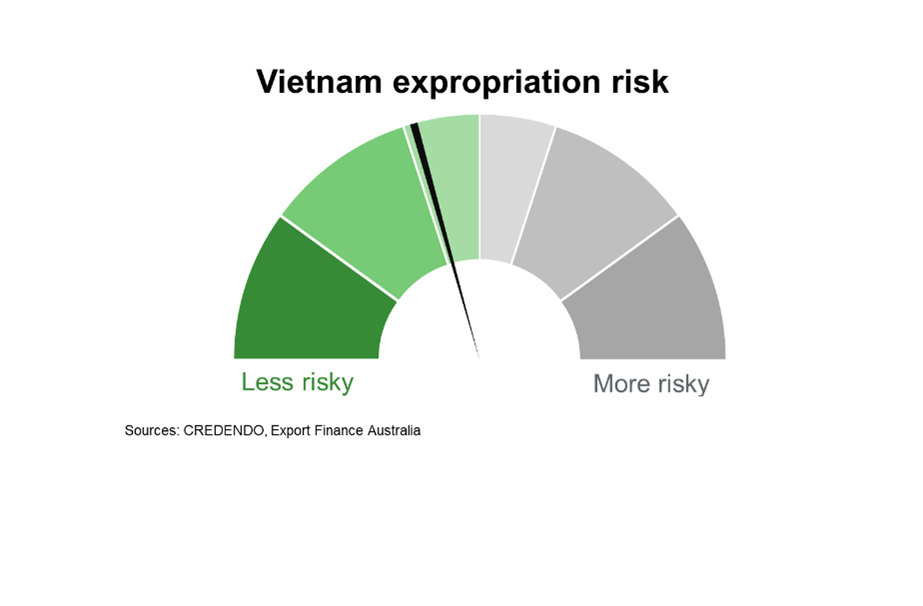

The risk of expropriation in Vietnam is low, consistent with the governance scores around the control of corruption and rule of law. According to the US Investment Climate Statements, the government can only expropriate investors’ property in cases of emergency, disaster, defence, or national interest. The government is required to compensate investors if it expropriates property.

Political risk in Vietnam is moderate. The political and security environment has a track record of stability, helping to provide a conducive environment for doing business. The government’s anti-corruption drive is positive for governance and institutional strength, though it is also contributing to slower policy implementation. Territorial disputes in the South China Sea remains an ongoing risk to Vietnamese relations with neighbouring countries, including China.

Bilateral Relations

Vietnam was Australia’s 12th largest trading partner in 2022. Australia’s total two-way trade with Vietnam in 2022 was valued at nearly $26 billion, up 43% from 2021. Australian exports to Vietnam are dominated by coal, but also include cotton, wheat, iron ore, and education-related travel. Goods imports consist mainly of telecommunications equipment, footwear, monitors, projectors and TV’s, footwear and crude oil.

Vietnam’s growing economy and burgeoning middle-class present significant opportunities for Australian exporters, including coal, LNG, iron ore, wheat and meat. Services—including education, professional and technical services—are also well positioned to capitalise on these opportunities. Vietnam is part of a network of Free Trade Agreements, including the ASEAN-Australia-New Zealand Free Trade Agreement (AANZFTA), Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) that all support bilateral trade.

Vietnam was Australia’s 7th largest source of foreign students in the year to September 2023. Australia is a leading education destination for Vietnamese students, with more than 35,000 Vietnamese students studying in Australia. Australian exporters can benefit from growing Vietnamese demand for education and training services in areas such as English language, business and management and information technology. Vietnamese student enrolments are well above their pre-pandemic levels, reflecting continued development of the Vietnamese economy and growing middle class that is boosting demand for higher education, particularly in Australia.

Tourist arrivals from Vietnam have increased substantially following the easing of international travel restrictions, surpassing pre-pandemic levels. Rising incomes are supporting growing Vietnamese demand for Australian tourism. A competitive Australia dollar and another year of recovery in international travel should support further demand for Australian tourism, and broader services exports, in 2024.

Before the pandemic hit trade and investment flows, bilateral investment between Vietnam and Australia increased strongly alongside growing foreign trade. Australian investment in Vietnam has picked up after the pandemic. Australian companies that have invested in Vietnam include BlueScope Steel and QBE. Vietnam’s foreign direct investment-led growth provides opportunities for Australian companies to increase investments in renewable energy, infrastructure, education, manufacturing, agribusiness, logistics, financial services and professional services. Vietnamese investment in Australia is small at around $440 million.

Useful links

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade

Austrade